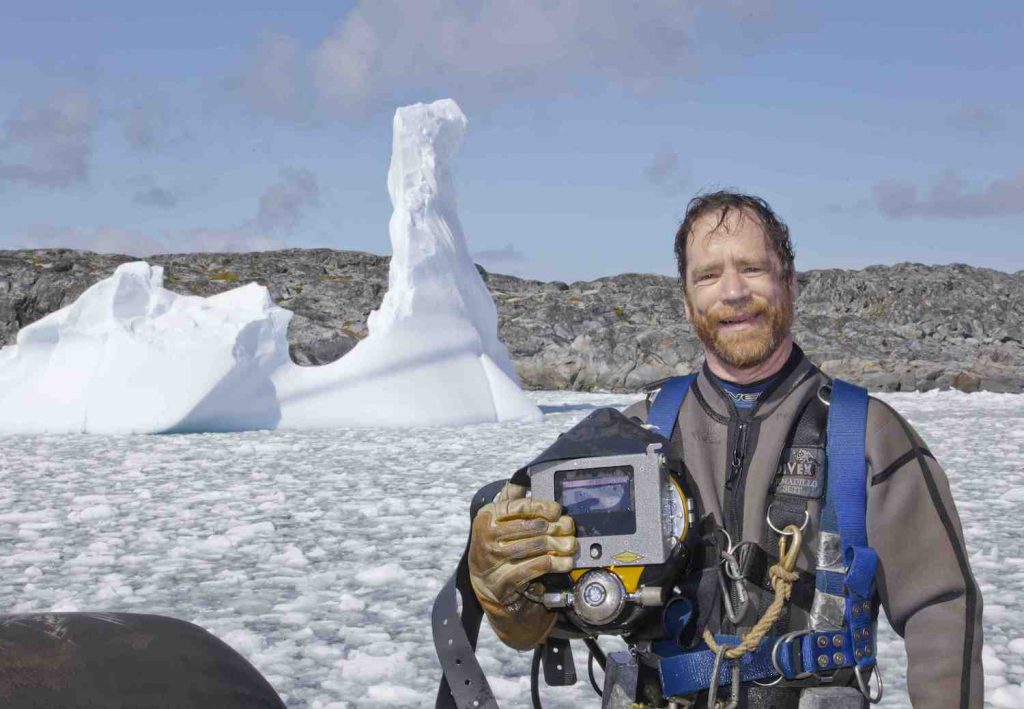

Antarctica is certainly not a normal location most people consider when it comes to dive destinations. White sand beaches and tropical waters are replaced with flat sea ice and unfathomably cold temperatures–especially when it comes time to jump in the water. As for Dive Supervisor of the U.S. Antarctic Program, Rob Robbins, it’s as normal as breathing through a regulator.

Robbins began his career as a student at Florida Institute of Technology in their Underwater Technology Program and then worked in the Gulf of Mexico for Sante Fe Diving Co. Later, he began the first of his 38 years of commercial and scientific diving in Antarctica for the U.S. Antarctic Program (USAP) installing the sea water intake and sewer outfall at McMurdo and Palmer Station. Now with nearly 2,100 logged dives in the earth’s southern most continent, Robbins has been honored with the Conrad Limbaugh Award for Scientific Diving Leadership by the American Academy of Underwater Sciences.

In an attempt to get a small glimpse into what it takes to spend decades diving one of the coldest locations on earth, we asked Robbins to share about his experiences, challenges, and honors:

After 38 years of diving in Antarctica, what keeps you excited to dive each day?

There is simply no dive I make at McMurdo Station where I don’t sit at the hole and say to myself, “Sweet! I can’t believe I get to do this!” I guess the main thing that keeps it exciting is the incredible beauty under the ice. Plus, the work we do is very rewarding. Helping a variety of scientists with their projects, filming for various media projects or getting back to my diving roots of doing underwater construction projects like welding, is all super fun. Actually, working with people new to diving under the ice has also helped. A few years ago, as part of our Artists & Writers program, we had a painter diving with us. Seeing the underwater world of McMurdo Sound through her eyes really reminded me of how special the place is.

What is the most challenging part of being a diver in Antarctica?

One might think it is dealing with the cold. In truth, you just get used to it. That is not to say we aren’t constantly looking for ways to keep our hands warm. We are. And any manufacturer out there can take this as a plea! Truth is, the most challenging part of our jobs as dive safety professionals in Antarctica is the same as anywhere else in the world: dealing with divers who are not as skilled as the situation requires. Diving in the extreme cold and under a ceiling is advanced diving by any definition. Our minimum requirements for dive authorization are relatively minimal. Some people are simply not up to the task when they arrive in McMurdo. People who are new to dry suit diving may not have their buoyancy control skills honed to the level required. I would say the most challenging situations I have been in are the few times when I have had to drag divers, who have lost control of their buoyancy, back to the access hole. It has only happened a few times but it is unnerving to say the least.

Can you describe what it is like to live in Antarctica?

In many ways, living in Antarctica is like going back to college. You live in dorms, you have a roommate and you eat at the one dining facility. There is no one in the U.S. Antarctic Program who is not somehow employed by the program, either as a grantee on a funded science project, or as part of the support staff. There are no dependents, only employees. I am normally there during the Austral summer. The diving typically takes place between late August and early December, at which time the sea ice surface becomes mushy and not usable for travel out to various dive sites. Also, a plankton bloom happens about that time which reduces the underwater visibility from many hundreds of feet to just ten to twenty feet. For these reasons, diving is greatly curtailed at that point. Ambient temperatures range from a low of about -40°F (-40°C) in August to above 30°F (-1°C) in December. Daylight changes from just a few hours in August to 24 hours per day by October where it remains until long after we leave at the end of summer. I have spent two winters in McMurdo. The 24 hours per day of complete darkness for several months is challenging.

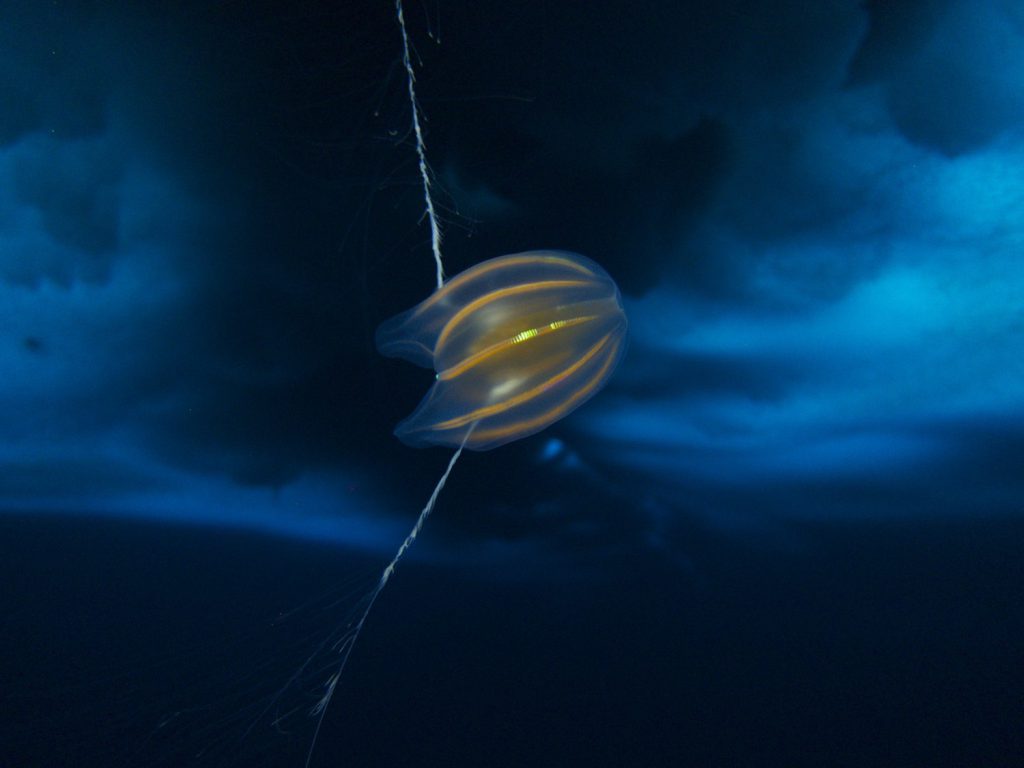

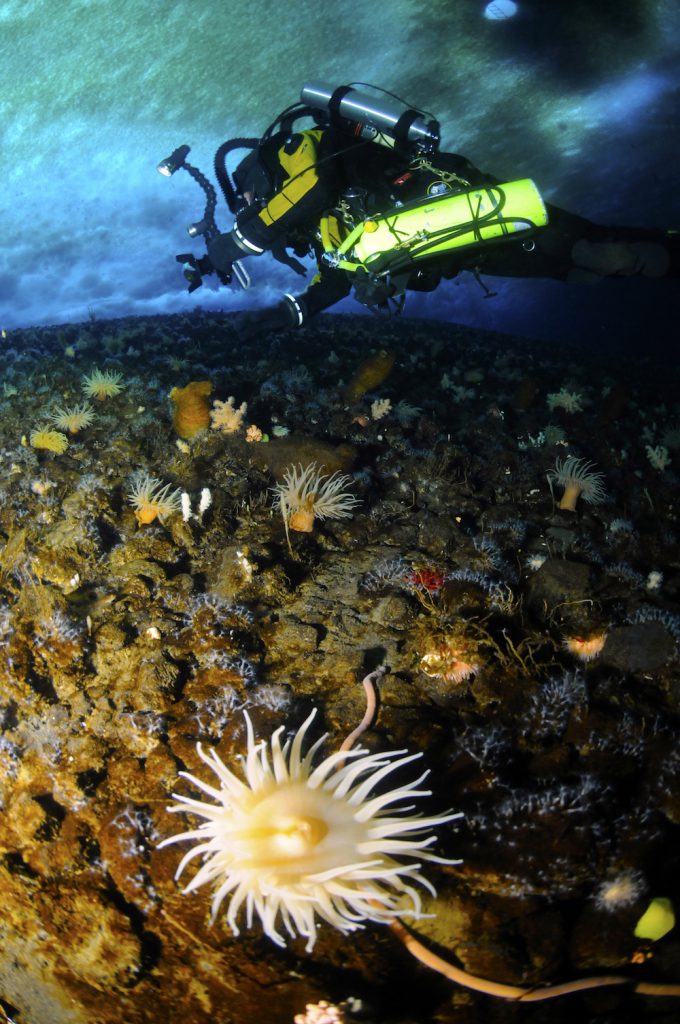

Can you describe the marine life?

The thing I tell everyone is that the difference between the lifeless surface of Antarctica, with various shades of blue and white, contrasts markedly with the different shades of blue and white under the ice. I’m kidding. Under the ice is teeming with life and color. That contrast is one of the very cool things about diving in Antarctica. The benthic invertebrate community is incredibly varied and lush. We see, or at least hear, Weddell seals on nearly every dive in McMurdo Sound. Their calls are eerily beautiful. Many organisms, which you’d see in temperate or tropical locations, have similar species in polar waters that take on a gigantic form. Huge sea spider and isopods are abundant and very, very cool. Giant barrel sponges are everywhere. Jetty fish, ctenophores, pteropods and other pelagic life are everywhere in the water column making ascents and safety stops just as fascinating as working on the bottom.

What do most people not know about diving in Antarctica?

I’m not sure people know that the visibility in McMurdo Sound is normally in the 800 ft (244m) range. Just spectacular.

What do you enjoy most about cold water diving?

Enjoy the cold? You’re kidding, right? I guess I have to say one aspect I like about diving in McMurdo Sound is that we normally drive a tracked vehicle over the flat sea ice and dive through a warm hut. No bouncing boat, no sea spray.

What has been the most interesting study you have lead over the years?

Part of our job is to facilitate the underwater work for a myriad of science projects. This might mean just doing checkout dives for the project’s divers, acting as the buddy for a scientist, or doing the underwater work for projects that need diving but do not deploy their own divers. We don’t initiate the science. That being said, I find most of the science projects we work with to be really interesting. It’s rewarding to be able to show a Principal Investigator where they can find the specific species of sea spider they are looking for, or to work with an AUV that is a prototype of a machine that might, one day, be sent to Europa to explore under the ice on Jupiter’s moon. The work is quite varied but all interesting.

What type of special equipment do you need to dive in such frigid temperatures?

The only really specialized piece of equipment we use are the regulators. We have done relatively exhaustive testing to find regulators that work reliably in the 28.5°F (-2°C) water of McMurdo Sound. We currently issue Sherwood Maximus SRB-7600 regulators. They have a freeflow rate of somewhere well under 1%.

What would you say is your biggest accomplishment as a scientific diver?

Having kept the couple hundred science divers, who have made over 13,000 dives under Antarctic ice, safe, productive and happy has been a huge accomplishment. Having made over 2000 of those dives myself has actually just been a bonus. Becoming friends with many of those divers has been a real treat.

What is the most unique or memorable experience you have had diving in Antarctica?

Being in the water with Orcas while helping with the PBS Nature film Under Antarctic Ice was awe-inspiring. Having a Leopard seal slam into me while I was welding on the pier at Palmer Station was very memorable. But it may have been the first dive at a place we call Evans Wall and seeing the giant soft coral Gersemia antarctica, which was not known to be on the eastern side of McMurdo Sound, that was my most memorable.

Congratulations on earning the Conrad Limbaugh Award for Scientific Diving Leadership by the American Academy of Underwater Sciences. What does this honor mean to you?

Having the members of AAUS vote to honor me with the Conrad Limbaugh Award was very special. My background is in commercial diving and I still love to do underwater welding and other construction tasks. Even though the vast majority of my diving for the past couple decades has been doing underwater science, I still have a hard time considering myself a scientific diver. Having the community honor me in this way is super meaningful.

Love ice diving? Check out these Top Ice Diving Destinations and learn more about the PADI Ice Diver certification.